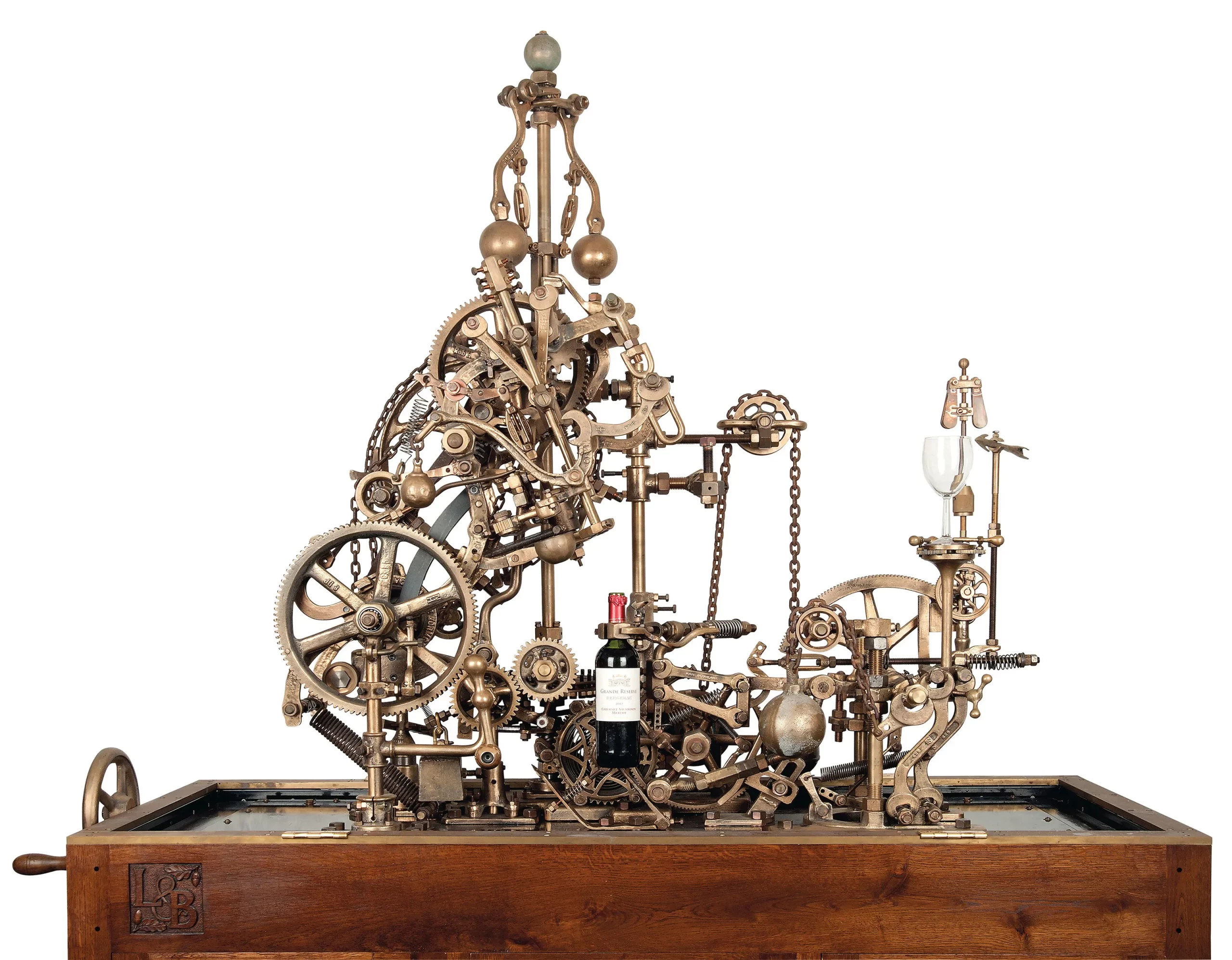

I here submit to you the essential outline for Victorian science fantasy, a.k.a. steampunk fiction: Rob Higgs’ “Corkscrew”.

‘How, in God’s name,’ you might ask and be rightly justified in doing so, ‘could such a device qualify as an exemplar of any sort of literary endeavor?’

Allow me:

As discussed in Steampunk is . . . , this niche subgenre of science fiction is intended to be far more than vintage sci-fi, although it can be only that and naught else. It can be, to no shame whatever, paranormal romance set in Century XIX with or without the addition of clockwork or coal power. Likewise, it may be historical romance with those same accoutrements. But in order for prose fiction to accomplish the definitive rebellious implications of steampunk fiction, the author might do well to consider the application of such model as the machine displayed in the accompanying demonstration.

After watching the video, please consider the specifications suggested below.

As stated in the post mentioned above, the punk portion of steampunk fiction’s christening is no inconsequential syllable. Punk implies a certain defiance, albeit, in this case, by circuitous means. Steampunk celebrates the shortcomings of technology through presentation of advancements that never could have occurred. The London of the 19th century proffered a glorious hope in many of its several wards while others can be described as nothing short of dystopian and apocalyptic.

Likewise, steampunk stories may, are allowed to, and, as is here suggested, might be expected to proffer similar dichotomy through the intentional rejection of certain rules presently considered dogma among the gatekeepers of the publishing industry. Passive voice; sentence, paragraph, and chapter length; the embrace and nurturing of cliche; et cetera may, along with clockwork and steam-powered fancies that intentionally defy the physical laws of their own foundations, represent a world of vastly unattainable luxury. As well might the very structure of story be so delightfully convoluted as to challenge its reader for the express purpose of doing so.

In the heart of the Century XX, when mechanization and industrialization yet ruled supreme and infallible, prior to the atomic dawn of the age of doubt, architects strived for their designs, whether offices, residences, or institutions, to act as machines. The form should follow the demands of the function. Every possible aspect of the structure should ease the lives of its users. Ornamentation was stripped away, as it served no functional purpose and lent nothing to convenience. Money was better spent on temperature and lighting controls. The world had moved beyond even the volutes and filigree cast in the iron plates of machinery of the Victorian age.

But then the great bombs dropped, and man proved his ability to destroy on a wholesale level, without discretion. Young people began to doubt the value of offering up their lives for the greater good in hope of a better tomorrow. The most vocal among them formed the punk movement and coined its fundamental premise: “If you’re not angry, then you’re not paying attention.” And a few architects decided that the designed and built environment should cease catering to the comfort and convenience of its users. Instead, they should be challenged by their environments. The design should serve itself more than it served its users.

Several of the great founders of steampunk fiction structured their stories likewise to the designs of those rebellious architects, and they produced stories that mimic Rob Higgs’ “Corkscrew”. One great example of this style of structure is James P. Blaylock’s novel Homunculus. This story has an alarmingly broad cast of characters that push and pull each other. They impose upon each other and react to each other precisely as the many cogs and pinions of Rob Higgs’ device do. And, like the Corkscrew, the story needn’t necessarily be so complex. Characters could be combined, as is often done to simplify a story and make it easier for the reader to take in. Publishers press authors to cater to the fast pace of the world and the resulting short attentions of potential readers with shorter chapters, paragraphs, sentences, and even novels. Though published all the way back in 1986, Homunculus was already a work of drawn complexity, challenging this notion of catering to the lowest expectations. Yet its resolution is delightfully simple, thereby magnifying its own complexity.

Many steampunk authors have followed Blaylock’s example and created intentionally complex plots for their novels. And it should be no great wonder that such is the case when we consider that exactly the same approach is implemented by makers and designers in the production of hats, clothing, vehicles, and machinery. Outlandish complexity, blatant impracticality, and lavish absurdity are the essential traits of all things steampunk.

But isn’t it amusing that we engage in such flippant frivolity to celebrate the Victorian era when its essential motive was reaction against the flippant frivolity of its romantic predecessors? Absolutely not! For by such irony we not only accomplish but also magnify the rebellious intentions of steampunk fiction and of Victorian science fantasy.